Will Pakistan’s New EV Policy Work?

Pakistan appears to be on its way to an economic turnaround. The improved macroeconomic numbers seen across manufacturing, agriculture and current account platforms are leading to concerted efforts towards clean energy.

1. Electric Vehicles (EVs) – No

Other Choice

EVs are critical for a country like

Pakistan, which faces consistently

worsening levels of smog year

after year. So much so that it is

now being referred to as the ‘fifth

Pakistani season’. In this context,

automobiles account for nearly a

quarter of the harmful greenhouse

emissions, with Punjab alone

garnering 43% of the total air

pollution load. Projections suggest

that by 2030, approximately

65-70% of the population will be

living in urban areas, leading to a

further increase in transportation

requirements and exacerbating

the environmental burden.

An emphatic move away from conventional vehicles to EVs would cut down Pakistan’s $1.3 billion import bill on fossil fuels and heavy carbon footprint, leading to zero direct greenhouse emissions, to eventually becoming a fossil fuel-free society. As a nod to these pressing environmental and economic challenges, the Engineering Development Board (EDB) has formulated the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Policy 2025-2030, with the singular objective to transition the transportation sector to EVs in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, lower reliance on fossil fuels and develop green technology.

2. NEV Policy 2025-2030

The 2019 EV policy hardly

achieved anything. Targets such

as the transformation of 3,000

idle CNG stations into electric

vehicle charging stations, or

sales of 100,000 electric cars,

never materialised. What is

different in the new policy, and

will it work this time? Key goals

include a significant reduction

in greenhouse gas emissions,

decreased reliance on imported

fuel, and the stimulation of

domestic green technology. The

NEV sets ambitious targets,

aiming for 30% of all new vehicle

sales to be electric by 2030, with

an even more enterprising goal

of 90% by 2040 and a longer

term vision of achieving 100% EV

adoption by 2060.

The policy charts out a three stage, broad-based plan to guide the ambitious transition. Phase I, spanning from 2025 to 2030, will focus on building the EV infrastructure – a widespread network of charging stations and battery swapping facilities, alongside initiatives to create public awareness about EV positives and practicality. Phase II, from 2030 to 2035, will concentrate on nurturing consumers further exacerbating affordability as risk-averse banking practices in Pakistan local EV manufacturers and expanding their adoption across the urban and rural breadth of the country. Finally, Phase III, from 2035 to 2040, will aim for a full scale transition to affordable EVs, facilitating their mass adoption. AI and machine learning will be employed to predict and project EV adoption trends, infrastructure needs, and the economic aspects of the transition through deep analysis of mined, granular data. In terms of financials, the policy recommends purchase subsidies to offset the initial high cost of EVs, the reduction of import taxes on EV components and vehicles, and tax exemptions to augment adoption. Apart from achieving the obvious climatic benefits of moving away from fossil fuels, the policy stresses battery recycling and disposal to ensure environmental protection and promote a circular economy.

3. Will the NEV Policy 2025 Work?

• No Detailed Implementation Roadmap

Analysts assess that the policy is

‘all talk, little action’ and lacks a

detailed implementation roadmap,

strategy, risk mitigation plan, or

defined timelines to realise the

targets, all of which portend

execution delays and inefficiencies.

There is over-reliance on fiscal

incentives and no attention is given

to how these will integrate and

impact the current energy and

transport policies.

• Economic and Financial

Barriers

Currently, EVs

in Pakistan are priced

approximately 1.6 times higher

than comparable internal

combustion engine (ICE)

vehicles. This makes EVs

inaccessible to an enormous

segment of the population.

With the IMF hawk eyeing our

financial system, scowling

at the idea of subsidies and

pushing for a tariff rationalisation

programme for industry, any offer

of subsidies or tax relief would

be dicey. Additionally, limited

access to financing options for consumers further exacerbates affordability as risk-averse banking practices in Pakistan currently restrict the fluid availability

of consumer financing for EVs.

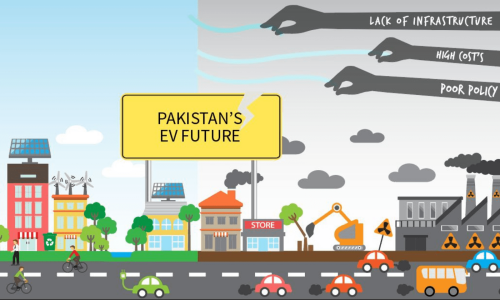

• Infrastructural Deficiencies

Charging stations are limited and

are concentrated in major urban

centres, with an estimated 40% of

these reported to be non-functional.

This sparse network leads to

anxieties among potential EV

users, particularly in the absence of

charging facilities in remote areas,

further undermining consumer

confidence. While Pakistan is

currently in a surplus power

generation capacity, the distribution

companies (DISCOs) have

capacity and load management

problems, while the existing grid

will require substantial upgrades

to meet significant increases

in electricity demand from EV

charging – another tall order.

• Consumer Acceptance

There are misconceptions about EV

performance, battery life and

maintenance costs, leading

to deterrence. There is also

a perceived inadequacy of

charging infrastructure.

• Local Manufacturing Hurdles

These, as well as the lack of a

reliable supply chain, are serious

problems. Can the domestic

industry ramp up EV component

production and supply in the next

five to 10 years? Sadly, at current

resources, no. Imports will only

bleed the national exchequer,

leading to higher costs and

increased vulnerability to global

supply chain disruptions.

• Regulatory Gaps

Federal and

provincial regulations conflict and

are confusing for both investors

and implementers. Responsibilities

for the control of crucial aspects

such as battery safety standards

and charging infrastructure

regulations remain unclear.

Registration processes for EVs

are cumbersome, discouraging

potential buyers. This lack of a

unified, comprehensive regulatory

framework is likely to create

uncertainty and hinder investment

in the EV sector.

These are the reasons why the last EV policy failed, and the current one seems similarly hollow and without substance in the absence of a solid transitional and regulatory game plan.

Nevertheless, the NEV represents a basis for EV launch, and there are some signs the policy may succeed. At the very least, the policy devises a three-phased approach that does allow for a gradual and systematic development of the foundations for EV adoption.

Pakistan’s current surplus energy landscape can spare electricity to power a growing fleet of EVs. The off-grid solar systems boom in Pakistan offers growing potential for decentralised and sustainable EV charging solutions.

Within the NEV policy, the government can refer to tested global practices and strategies from China and Thailand to develop effective financial incentive mechanisms, including subsidies, low-interest financing schemes and tax relief at consumer and investor levels. The NEV would do well to proactively push for alignment between federal and provincial government bodies, investors, manufacturers, energy providers and infrastructure developers, as well as consumer groups and public advocacy organisations to ensure synergised policy implementation and regulation. A robust charging infrastructure is critical and makes EV ownership practical for consumers. The government’s plan to establish 3,000 charging stations by 2030 can only be achieved by deploying public private partnerships.

EV adoption in Pakistan is negligible, with the two-wheeler segment taking 70% of sales thus far. However, momentum is up with 50,000 such motorcycles produced during FY 2023-24, up from 15,000 in FY 2022-23. As of February 2025, the EDB has granted licenses to over 57 manufacturers. Chinese brands such as BYD, BAIC, Changan, JAC, Great Wall Motors (GWM), MG, FAW and Chery have entered the fray, both as direct imports and joint venture mechanisms.

Despite this positivity, the NEV policy will succeed only if armed with a definitive, time-bound strategic plan that addresses infrastructure, manufacturing and financial incentives, streamlines implementation and encourages investment. Post the lethargy of the last EV policy, it is time to learn from missed boats and find the right place for Pakistan in a prospering global EV ecosystem.

Mazhar M. Chinoy has led the marketing services function for a leading multinational automobile company and has been a director at LUMS. mazharmchinoy@yahoo.com

Comments (3) Closed