Building an Electric Future

Pakistan’s transition to electric vehicles (EVs) is critical. Yet, the pace of EV adoption remains limited and inconsistent. To understand why this is so requires a closer look at national policies, gaps in infrastructure, market dynamics and the key decisions needed to shape Pakistan’s mobility future.

Transitioning to EVs is a vital economic need, and although public discourse often highlights electric cars, the real potential lies in electrifying everyday vehicles used by ordinary citizens. This shift in focus is essential, particularly if we want to create an EV ecosystem that is locally manufactured, financially accessible and suited to Pakistan’s urban and rural transport needs.

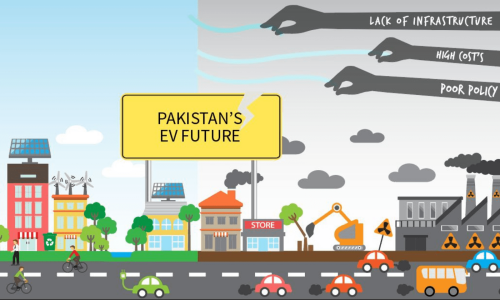

The National Electric Vehicle Policy (NEVP) 2020 marked a significant step forward with the government stating its intention to electrify 30% of all vehicles by 2030. However, progress has been slow, particularly in the two-wheeler segment. The problem is not just demand but the kind of supply the market is incentivised to create, and a major flaw in the policy is the failure to differentiate between assembly and genuine manufacturing. The current incentive structure favours the import and assembly of completely knocked down (CKD) kits rather than the development of local manufacturing capabilities, an approach that drains foreign exchange reserves, stunts local technological advancement and hinders the creation of skilled jobs. Continuing in this direction means Pakistan risks becoming a mere assembly line for foreign brands rather than a hub of innovation and industrial growth.

he most practical and impactful entry point for mass EV adoption is the two-wheeler market. Given that over 20 million petrol-powered motorcycles are already in use, an electric alternative will significantly reduce fuel consumption and urban emissions. Yet, the market is flooded with moped-style electric scooters, which are limited in their load capacity and unable to carry multiple passengers or heavy goods (unlike traditional bikes). Many of them also use underpowered motors and low-quality batteries (lead-acid or so-called ‘graphene’) that offer limited range and short lifespans. However, despite their limitations, electric scooters serve an important niche, particularly for women. Lightweight and easy to operate, they are opening doors to mobility and autonomy for women who lack access to traditional vehicles. In this context, these scooters represent a valuable component of a gender-inclusive EV future.

One of the overriding arguments against EVs is the lack of long-range capabilities, suggesting that unless a vehicle can go from Lahore to Karachi on a single charge, it is not viable. This is a flawed perspective. Over 80% of daily trips in Pakistan are under 50 kilometres, and electrifying these short, routine commutes could dramatically cut emissions, reduce the oil import bill and improve public health in congested urban centres. The focus should be on everyday utility, not exceptional journeys.

Given that the public charging infrastructure is still in its infancy, battery swapping has emerged as a practical solution for high-utilisation users who travel over 90 kilometres a day – allowing them to exchange depleted batteries for fully charged ones. Furthermore, the battery-as-a-service model reduces upfront costs, making EV ownership affordable for low- and middle-income individuals.

Another misconception is that widespread EV adoption hinges on the rollout of an extensive car-charging infrastructure. In reality, infrastructure follows demand (not the other way around), and although high-voltage, grid-heavy charging networks for cars are expensive and slow to implement, and three-wheelers require far simpler systems. Such vehicles can be charged using basic home sockets or through scalable battery swapping stations, making them more adaptable to Pakistan’s urban landscape. Prioritising car charging networks in a resource-constrained economy is both inefficient and exclusionary.

Sceptics argue that because Pakistan’s electricity grid relies heavily on fossil fuels, EVs are not significantly cleaner than petrol vehicles. However, electric motors are inherently more energy-efficient than internal combustion engines, even on a coal-based grid. Furthermore, Pakistan is increasing its investment in renewable energy sources, and as the grid becomes greener, the environmental benefits of EVs will grow. Dismissing EVs due to today’s imperfect grid is short-sighted; progress must start somewhere.

Government policies have focused on promoting electric cars that are financially out of reach for most Pakistanis. This car-centric strategy misaligns with the realities of public transportation and Pakistan’s economic goals. The reality is that only a small fraction of households owns cars, and the vast majority depends on motorcycles, rickshaws or public transport. Moreover, electric cars require significant subsidies and expensive infrastructure. For the cost of one electric car, the government could support the deployment of 10 to 15 electric two-wheelers, thereby delivering greater benefits in terms of emissions reduction, fuel savings and urban mobility. Furthermore, because electric cars have limited daily usage, their negative environmental impact is lower compared to commercial vehicles with high mileage. If the goal is maximum impact, the focus must shift toward electrifying the vehicles used by the many, not the privileged few.

Today, electric two- and three-wheelers remain financially out of reach for most gig-economy workers and low-income households, and traditional banking systems have failed to respond to this emerging opportunity. Rigid credit requirements, lack of collateral and long approval processes exclude the very people who would benefit the most from owning an EV. In this context, financial institutions must develop tailored lending products for EV buyers – including low-interest loans, flexible repayment terms and bundled service partnerships with EV manufacturers. Without targeted inclusive financing, EV adoption will remain a privilege rather than a widespread solution.

A single electric bike can reduce up to one ton of CO₂ emissions annually; scaled, the environmental impact becomes significant. From an economic standpoint, riders can save up to 60% every month on fuel, and with fewer mechanical parts to maintain, they benefit from lower operating costs and greater income stability. Cleaner air also means lower public health expenditures and fewer respiratory illnesses, especially in cities.

To fully realise the potential of EVs in Pakistan, several shifts are necessary. Policy incentives must reward genuine local manufacturing, not just superficial assembly. EV models should be designed with local needs in mind – rugged, powerful and capable of replacing petrol bikes. Financing must be inclusive, with products tailored to informal workers and gig economy participants. Gender equity in mobility must be promoted through vehicle design and adoption programmes. Finally, the widespread myths about the charging infrastructure, range anxiety and grid emissions need to be challenged through public education and on-ground demonstrations.

Pakistan is at a crossroads. The transition to electric mobility offers not only environmental benefits but also a pathway to economic self-reliance, industrial growth and social inclusion. This transformation must not be limited to the affluent or early adopters. It must serve riders, informal workers and marginalised communities. By prioritising locally manufactured, affordable and fit-for-purpose EVs (particularly two- and three-wheelers), Pakistan can lead in shaping a cleaner, more equitable transportation future. The road ahead is electric. How we build it will determine our resilience, prosperity and our role in the global clean technology movement. It’s time for Pakistan not to follow but to lead.

Ali Moeen Malik is co-Founder, ezBike.

Comments (0) Closed