Cover Story – The Prêt Effect

(This article was published in the Sept-Oct 2015 Aurora Magazine issue.)

Two decades ago, urban Pakistan was a pretty dull place in terms of branded shopping. There was barely any organised retail and the ubiquitously unflattering ‘free size’ kurta was the only option available to women who wanted reasonably priced ready to wear clothing. But then again, Pakistani women were more than happy to buy unstitched fabric, along with buttons, lace and piping and then take the lot to the tailor for a custom-made jora, even if the process was hassle-ridden at the best of times.

Textile giants like Al-Karam, Gul Ahmed, Nishat and many others flourished in this environment, offering a variety of designs in lawn, linen and cotton. Then came the lawn rush of the 2000s, which elevated this humble fabric to designer status with hoards of women thronging to lawn exhibitions, causing traffic jams and creating urban legends in their wake. In the midst of the frenetic pull and push of the exhibitions and frantic visits to the darzi, a sense of weariness was creeping in and it was quickly capitalised on by a handful of prêt wear brands that had the vision to foresee that women’s wear, at least in the major cities, had the potential to become an entirely different and more value added proposition.

A stitch in time

A pioneer of prêt wear in Pakistan, Generation was established by Saad and Nosheen Rahman in 1983, with one store in Lahore. Saad Rahman was in the business of exporting high quality garments to Europe and used his knowledge of textiles and apparel production to launch Generation. At a time when polyester was very popular in Pakistan, Rahman produced cotton ready to wear outfits in small, medium and large sizes, and became instantly popular with a small group of women.

More recently, Generation has launched a size 6 to make its clothes accessible to customers in their tweens. Ahead of its time in a country that wasn’t quite ready for prêt wear and with just two stores (one each in Karachi and Lahore), Generation remained a niche brand.

In 1999, a young Indus Valley graduate started small with a line of unstitched fabric, men’s kurtas and women’s kurtis with one store in Zamzama. The brand’s USP was a lightweight self print khaddar which came in a variety of colours. As Shamoon Sultan, CEO, Khaadi tells Aurora, his brand became an overnight success.

Read: Khaadi's multinational ambitions.

However, as the customer base was small and the retail sector was not very developed, Khaadi too remained a niche brand for a time. All the while other brands kept popping up; Chinyere by Bareezé, Daaman, Ego, J Dot by Junaid Jamshed and Sheep, to name a few; however, Khaadi kept pace with these developments and went from strength to strength, opening stores and offering innovative designs.

Read: 'Junaid Jamshed – A Shari'ah compliant brand.'

However, all this may have come to naught had it not been for two other significant developments. The first was the boom in the retail sector (currently worth Rs 50 million). Secondly the percentage of working women in Pakistan increased from 16.2% in 2000 to 24.4% in 2011, which means an additional seven million women joined the workforce in 11 years (Source: Pakistan Employment Trends Report, 2011). An increase in disposable income combined with limited time to deal with darzis who were facing delivery issues due to electricity shortages made the perfect case for a ready to wear revolution, which was supported by an increase in the number of malls and shopping centres.

Thus the last four or five years have witnessed a boom in the ready to wear space with so many brands opening stores (Agha Noor, Beechtree, Eden Robe, Ethnic, Kapray, Limelight, Origins, Sapphire, Thredz, etc.) that it is hard to keep track of them all. But perhaps the most telling sign that prêt wear has truly ‘arrived’ is that the big textile mills (Al-Karam, Firdous, Gul Ahmed, Nishat,) have also launched ready to wear lines, in parallel to their existing unstitched fabric collections, to keep pace with market trends.

Made to measure

Unstitched fabric accounts for over 90% of women’s clothing sales across Pakistan, while ready to wear is estimated at just half a percent of the retail market, catering to two to three million customers in a country of 200 million. In order to ensure that their brands cater to the wider mass market, most clothing brands – whether they started out off as purveyors of fabric or with prêt as their area of expertise – sell unstitched fabric along with ready to wear. (There are of course exceptions; these include Daaman, Generation and Sheep that only do ready to wear clothing, but they remain niche brands.) However, it is prêt that is seeing major growth and for several brands, this is in the region of 25 to 40%. Ziad Bashir, Director, Gul Ahmed puts this in context by saying that “while our overall retail growth is 20%, apparel is growing at 38 to 40%.”

Aurora’s Fast Fashion Survey shows that Khaadi is the most sought after ready to wear brand, in addition to being considered the best value for money. Sultan says what sets Khaadi apart is “the pricing strategy, the retail experience and design,” clearly suggesting that it is this triumvirate of elements that brands need to work on in order to achieve a measure of success in an extremely competitive market, where the barriers to entry are higher than they were even one or two years ago.

The problem, as Farrukh Mian, Director, Textile Links elucidates, is that “every new brand wants to be like Khaadi. They assume that because they have opened a store in Dolmen Mall they will achieve instant success.”

Most brands would prefer not to admit this, and in certain cases it may also not be true, but there is most certainly a sense of sameness in the ready to wear market. Practically all the brands cater to young women (under the age of 35), they all tout the quality of their fabric as a USP and have roughly the same pricing strategy. Although these offerings are in line with what most ready to wear customers want: a trendy kurti or outfit at an affordable price from a brand that offers good customer and after sales service – there is no room left for differentiation.

Priced to perfection

Despite its clientele hailing from the higher SECs of society, the ready to wear market is extremely price conscious. Aurora’s Fast Fashion Survey found that the majority of respondents (30.9%) were comfortable paying between Rs 2,100 to Rs 2,600 for a kurti and the industry has priced itself accordingly, with prices ranging between Rs 1,900 and 3,000 for a basic printed kurti. Although a lot of people in Pakistan would not consider this ‘cheap’, it reflects a democratisation of readymade fashion (a market that was previously either inhabited by low priced, badly designed clothing or by very high-end designer wear) by making it accessible to a larger group of customers – and is a result of the rationalisation of prices that took place last year.

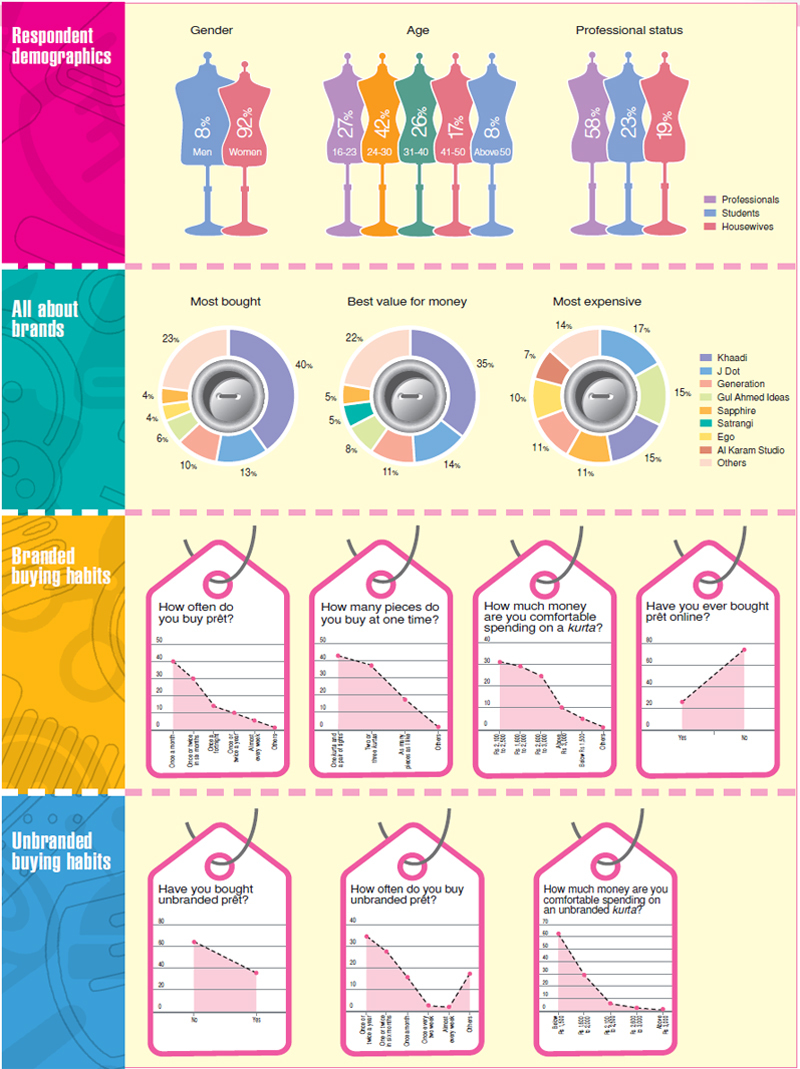

The Aurora Fast Fashion Survey

Aurora conducted a survey via social media to uncover buying habits and attitudes towards ready to wear brands. 500 people (mostly women) responded to our questions over a period of one week. Here are the results.

(Click here to enlarge)

The general perception among customers is that Khaadi reduced its prices in 2014 and then the other brands followed suit. What really happened was that Khaadi (as a result of business growth) had achieved certain economies of scale and decided not to increase its prices. By virtue of being the market leader, other brands were forced to match Khaadi’s prices. But not all have followed suit.

The ready to wear brands backed by textile mills are generally priced higher with basic kurtis ranging between Rs 2,900 and Rs 4,000. By virtue of having their own vertically integrated units, where all the processing from cotton spinning to weaving to the production of the cloth is done in-house, these brands say they are unable to make the price reductions in their finished product in the way that brands who source their fabric from other vendors do. However, their perception of how this higher price impacts their business differs.

Acknowledging that they are at a disadvantage compared to other ready to wear brands, Faisal Hidayatallah, Marketing Manager, Al-Karam, explains that although AlKaram Studio (the company’s retail arm) made a correction in the prices of unstitched suits last year in order to bring them to market level, “we have yet to do the same for prêt wear, because coming down to the current market price would mean compromising on quality. However we do want to create a product for this price conscious audience as well.”

Bashir at Gul Ahmed has a different view. He believes that customers are still willing to pay for quality and cites the fact that Gul Ahmed’s fabric will not wear out after several washes as a major USP.

Some customers may pay extra, but for the majority, ready to wear has become synonymous with disposable fashion. Pioneered by British high street brands such as Primark and New Look, disposable or fast fashion refers to clothing that people buy and wear a few times before disposing of it and buying something else. Hidayatallah says this is precisely what is happening in Pakistan.

“People don’t want to repeat an outfit too often and nor do they care about retaining it, so the average life of an outfit is two weeks maximum.”

Khadija Rahman, Director, Generation says she believes there are some Pakistani brands which are compromising on quality and producing disposable fashion (although they don’t openly admit it) “and this gives them an edge, because they can sell at even lower prices. Generation as a brand believes that we are also in the fast fashion trade but we don’t want to do it at the expense of our quality.”

Rumours abound that one of the ways brands lower the cost of production is by sourcing Chinese and Indian cloth which enters Pakistan through grey market suppliers.

Afshan Ahmed, Admissions and Job Placement Manager, Textile Institute of Pakistan (TIP), says that former students from TIP who are currently working for large prêt wear brands speak about how these brands source their cloth from places like Rabi Centre, which are hubs for smuggled fabric.

Designing to sell

The tension between price and quality is an ongoing affair but when it comes down to it, customers buy based on what they see: i.e. the design. Unfortunately, when it comes to design there is an element of sameness and a definite lack of innovation. As brands work overtime to send several new designs into the market every week, they appear to be simply looking at what the competition is doing, changing a few elements and putting their pieces into production.

Therefore it is not surprising when Rahman says most brands “are just print companies that develop a lot of prints [geometrics, florals and digital] and then stitch them up into basic silhouettes.”

Sultan agrees that no one is trying to come up with their own identity. “I can tell if someone is wearing my own brand but it is becoming very hard to differentiate between other brands, and I doubt this will happen in the near future.”

Nevertheless, brands that differentiate are reaping the benefits. A classic case is Agha Noor, a brand started by two teenage sisters (Agha Noor and Agha Hira) in 2011. The brand has a limited retail presence (five stores in total) and the sisters were not well known in fashion circles prior to the launch of the label. Yet today Agha Noor is a tremendously buzz worthy brand and whenever a new collection is launched, a simple billboard or a Facebook announcement is enough to have women rushing to the stores to be the first ones to buy. The reason is simple; the Agha sisters use a fabric called ‘cotton net’ to produce formal and semi-formal outfits in a price range between Rs 3,500 and 4,000 and this has impressed everyone from the average customers to TV celebrities alike.

Another brand which has managed to take the market by storm is Sapphire, a collaboration between the Sapphire Group and luxury designer Khadijah Shah of Elan. Launched in 2014, Sapphire offers prêt wear and unstitched fabric and has a design philosophy that not only brings ramp fashion to prêt wear, but offers a variety of digital prints that are not your average geometrics or florals. Furthermore, Sapphire has always tried to create an interesting retail experience with fairytale like shops and windows displays that are changed regularly. Not since the launch of Khaadi has a ready to wear brand managed to capture the imagination of the market the way Sapphire has done (Mian says it has captured some of Khaadi’s market share as well). More mature brands like Khaadi and Generation are also innovating by entering the domain of western ready to wear with brand extensions like Khaadi West and Generation Flo.

Although all this goes to show that innovation in ready to wear will be rewarded, unfortunately most ready to wear brands prefer to stick to tried and tested designs in lawn, cotton, cambric and silk for the majority of their creations.

Another issues is that although brands are now hiring young graduates as designers from TIP, AIFD and Indus Valley to bring a new and fresh look to their product offerings, many of these newbies don’t understand what mass fashion entails.

“Young designers, especially from schools such as AIFD and Indus are inclined towards producing ramp fashion. They don’t understand the production aspect of design. If they design something and we can only produce 10 to 15 pieces a day, then there is no point to it. They need to have an aesthetic sense combined with a sense of commercial viability,” says Bashir.

TIP is trying to address the situation by offering degrees in Fashion Design Management, which says Ahmed, “combines fashion design with management courses to give students a better sense of the commercial aspects of the business.”

However, TIP’s batch intake is quite small (about 30 students) and not nearly enough to meet the growing demand from the prêt wear industry.

Clothes, clothes, everywhere

Another area where there is a shortage of trained resources is retail. Although brands offer in-house training for retail marketing and management, there are no degree courses available in Pakistan. This area is becoming especially important as prêt wear brands are investing significantly in expanding the size of their retail network to increase accessibility to their products.

Read: Adil Moosajee (Owner, Ego) in profile.

Sultan says new brands should not even bother to enter the ready to wear category without a 15 to 20 store model. Khaadi, for example, has 40 stores in 11 cities; J Dot has 62 stores in 20 cities, Gul Ahmed Ideas has 65 stores in 17 cities, Al Karam Studio has 22 stores in 12 cities and so on. However, there are several different retail models at work.

There is the Khaadi and J Dot model where these brands offer men’s wear, women’s wear, unstitched, kids wear, couture and other lines in each of their medium format stores. Brands like Gul Ahmed Ideas and Al Karam Studio offer unstitched fabric, prêt and home wares (in the case of Gul Ahmed) in larger format stores but they also have a huge countrywide network to distribute unstitched fabric. Then there is the Bonanza and Cambridge model; they stock prêt wear from Satrangi and Zeen respectively within their store network across Pakistan (Bonanza has 70 stores and Cambridge 24) but they also have a handful of standalone Satrangi and Zeen stores that offer ready to wear and unstitched fabric. Finally, brands like Agha Noor, Daaman and Sheep that deal solely in prêt, have a much smaller network of small format stores and are limited to the major cities. The only exception to this is Generation which, despite the limited size of its retail network has large format stores.

Most brands “are just print companies that develop a lot of prints [geometrics, florals and digital] and then stitch them up into basic silhouettes,” says Khadija Rahman of Generation.

Brands like Satrangi and Zeen are at an advantage by virtue of the fact that their parent brands already have an established network of stores and they therefore don’t have to spend too much on acquiring new properties as they can simply revamp existing stores. However, the disadvantage is that because these stores were established before the retail boom, they are not located in the current shopping hotspots.

Malls, which are increasingly the base of the retail culture in most major cities, offer premium spaces for ready to wear brands, albeit at premium prices. Mian says that the rent in high end malls like Dolmen Mall Clifton is between Rs 500,000 and two million rupees depending on the size of the shop, while in shopping centres such as Tariq Road, Bahadurabad and Clifton, rents range from Rs 50,000 to 200,000.

Despite the costs incurred, brands are eager not only to invest in new locations and stores, they are also interested in creating a ‘retail experience’. Concepts – such as visual merchandising (the use of attractive, seasonal themed shop windows to attract potential customers), creating attractive, colour coordinated store displays to catch the customer’s eye and using smaller aisles to continually engage the shopper’s interest (all in line with international practices) are being adopted by brands to stand out from the competition.

Eager to stay ahead of the rest of the pack, Sultan says that starting in November, Khaadi plans to change the concept of ready to wear retail by opening large format stores in the newer malls in order to take the retail experience to a new level. Given that Khaadi has always been an innovator, this will be an interesting area to watch.

In addition to expanding their brick and mortar presence in Pakistan and abroad (the UK and the Middle East in particular), prêt wear brands are establishing online stores as a way of targeting international and younger local customers with a penchant for online shopping. Most brands prefer to have their own online stores but others are using platforms like Daraz.pk and Kaymu.pk to push their merchandise and reach out to a larger audience.

Komal Dawani, Manager Marketing and Media, Satrangi at Bonanza, says online stores increase accessibility “and they are important to help figure out where we should open our next store as well.”

Read: 'A day in the life of Komal Dawani – Marketing and Media Manager, Satrangi.'

Bashir, however, offers a final, tempering word on expansion by saying that “it is not just about opening stores; it is about innovation, design and supply chain to ensure that the stores are filled with the right products and the right mix.”

Readymade Pakistan?

Ready to wear brands may be an integral part of Pakistan’s retail landscape, yet despite the strides made to develop this category in a relatively short span of time, there are questions regarding its growth. The first is whether ready to wear will ever become a nationwide phenomenon.

In Sultan’s opinion, there is a very clear bifurcation between prêt wear and unstitched customers and “only 10 to 15% of women buy both, otherwise it is either this or that.”

He adds that prêt is very much an urban phenomenon and even in the cities, it is mostly patronised by working women from the higher echelons of society; “those who are not working, are too thin or too large don’t buy ready to wear.”

The scenario in the rural and semi-rural towns is quite different. While all the major prêt brands have stores in places like D.I Khan, Mandi Bahauddin, Okara and Swat, unstitched fabric dominates sales there and “even if I priced a kurti at Rs 300, I would not be able to sell it there,” says Sultan.

This is all the more challenging for brands like Generation which do not sell unstitched fabric.

According to Rahman, “in certain parts of Pakistan people are not open to ready to wear or open to the styles people are wearing in the cities, so they prefer having their clothes stitched. Brands like ours cannot enter those markets and I think this will be a challenge for us.”

Even within the urban landscape, the ready to wear market will need to expand significantly in terms of the number of brands available in order to become a truly ubiquitous phenomenon. But with brands expanding retail networks, intensifying marketing and branding efforts and selling at even lower prices, the barriers to entry are quite high for new entrants. Despite this, Bashir believes that ready to wear will grow at a rate of 25 to 30% over the next five years. Sultan is less optimistic saying that “retail will grow very fast but as far as ready to wear is concerned, if it is two to three percent of the entire market now, it will go up to 10%.”

The ready to wear market has real potential and customers, despite having at least 15 to 20 good brands to choose from, are eager for more options. However, brands will need to create an individual identity for themselves instead of just following the market leaders. Brands like Agha Noor, Sapphire and even J Dot (with its Shari’ah compliant positioning) have shown that this is possible. It is time for others to connect the dots and take the ready to wear revolution forward.

Comments (4) Closed