The Master of Spices

First published in Aurora’s November-December 2005 edition.

Walking into Shan Foods is a culinary experience in itself; the pungent aromas of red chillies, cardamom, garlic and freshly ground cumin assail the senses, evoking images of sumptuous biryanis, delectable kormas, scrumptious chapli kababs and extravagant niharis and haleems. These dishes, an essential yet complicated part of Pakistani cuisine, can now be mastered by just about anyone who has access to a packet of Shan masala.

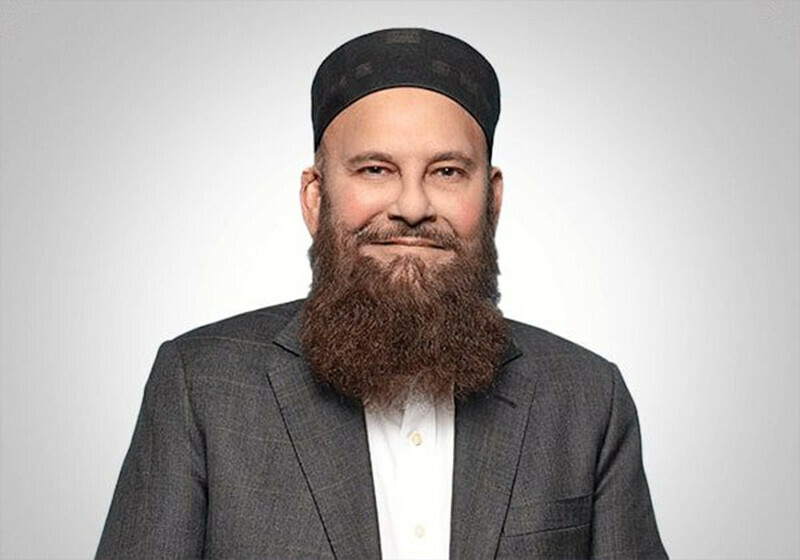

Shan’s product range is extensive; there are over 90 varieties, consisting of masalas, desserts, instant food mixes, pickles, etc., making it not only the market leader in Pakistan but also the brand of choice in the 47 countries to which it is exported. In spite of international acclaim, the company is renowned for its close-knit family environment. And nowhere is this more amply demonstrated than in the personality of the master of spices himself, a.k.a. Sikander Sultan.

Soft-spoken, but with a steely and commanding air about him, Sultan’s love for food in general, and spices in particular, was nurtured by a family of culinary connoisseurs. In a culture which discourages men from venturing anywhere near the kitchen, Sultan was capable of producing perfect gulab jamuns by the age of 10. He was also exposed to the family tradition of tikkia making early in life, a process whereby various spices are ground on a large pestle and mortar, shaped into kebabs with a hole in the centre, sun-dried and preserved for future use.

Already fascinated by the art of tikkia making, fate forced Sultan to try his hand at the discipline when his mother’s extended vacation left the family with a depleted source of tikkias. He recalls his younger sister’s failed efforts to recreate her mother’s handiwork with fondness and explains that none of the market-bought spice mixes were able to satisfy the family’s delicate taste buds.

Sultan converted his initial efforts into a weekend hobby, sitting under his father’s watchful gaze for long hours, experimenting with various types of spices and their quantities in order to obtain the perfect mix. Not only did he learn the properties of the spices, but he also received a crash course in spice mix preservation.

Subconsciously, these experiences were making an epicure out of Sultan, but it was not until he had pursued many other interests that he found his true calling.

He began his professional life as an independent filmmaker, directing training documentaries for clients such as PIA and Mohammed Farooq Textile Mills. A strong believer in giving back to society, Sultan simultaneously ran a film and theatre club for aspiring cinematographers at the Goethe Institute and also pursued an MBA.

At this time, he was introduced to Nadir Hussain of JWT, who taught him the basics of copywriting and scriptwriting. Putting these newly acquired skills to good use, Sultan directed a few commercials and even choreographed a highly successful fashion show in the early eighties.

However, Sultan’s exposure to advertising and filmmaking left him depressed. Struck by the general feeling that his clients were far more interested in the model representing the product rather than the creativity he could bring to the table, Sultan says he felt “more like a pimp than a professional”. This feeling, coupled with his mother’s inherent distaste for advertising, made his decision to quit a relatively simple one.

Sultan’s earlier experiments with spice mixes and his marketing degree had opened his mind to the possibility that there was a market for the product he was so passionate about. Acting on a hunch, the would-be entrepreneur bought Rs 40,000 worth of garam masala, had it ground and mixed to his specifications and sent it to his sister in the US. The mix was an instant success and Sultan was overwhelmed with orders.

Confident that this small triumph could be translated into larger numbers, Sultan sold his car, cameras and other equipment, hired a staff of five people and worked closely with his wife to test market three spice mixes before Eid-ul-Azha in 1981. Assuming that market stocks would last for up to a month, Sultan had to step up production instantly when retailers started asking for a larger stock before the end of the first week.

Using the family’s vegetable garden as his base, he hired five more people and worked round the clock in order to meet demand. A month into this hectic pace, Sultan realised he had hit the jackpot, and he and his wife created a range of 13 Shan masala blends that were first marketed in 1983.

In spite of its tremendous success, Shan was a cottage industry until 1994, when Sultan realised that it was no longer possible to continue doing business out of his small vegetable patch. Over the years, the number of blends has increased substantially and the product development still continues.

Sultan believes that the reason people appreciate the mixes is simple: “Every recipe mix we market starts out as something we develop for our own family. That being the prime objective, we are careful that we use only the best ingredients and put the product through the most exacting quality standards.”

Sultan explains that product development is a passion he and his wife share and slowly but surely, their children are also getting in on the excitement. In recent years, Shan has moved away from the tag of manufacturer of masala mixes and moved into pickles, pastes and desserts.

For all its achievements, the company remained advertising shy for the first decade and a half of its existence. Sultan explains that this is a direct result of his religious beliefs.

“I realise this goes against all the laws of marketing and advertising, but I believe that Allah, the unseen force, is responsible for our success. My philosophy is that if I use forces under my control, such as advertising, this will thwart Allah’s help.”

After many years of resisting advertising, Sultan eventually gave in to senior managers within the company, who initially suggested promotional campaigns, which began appearing in 2000 and more recently insisted that Shan carry out an image-building exercise.

This has come in the form of Shan Foods’ latest advertising campaign, titled Yeh rishta hai pyaar ka. Sultan explains that the company wanted to pay tribute to women, and to mothers in particular, who work selflessly to feed and care for their children, rather than showing off the product itself.

Having exhausted my bank of questions, Sultan introduces me to the latest in Shan’s rapidly expanding range: Fruit Chaat Mix. His serving suggestions include using it over fruit chaat or as a drink mix. Demonstrating the latter, he adds a teaspoonful of the mix to a glass of water and adds a dash of lime. With a twinkle of genuine excitement, he hands the concoction over and asks for my opinion.

Only one word comes to mind: “Spicy!”

Comments (0) Closed