Go Hybrid

I have always had a passion for all types of cars. Yet, when the electric vehicle (EV) fad started, I was a non-believer. The world was hailing EVs as the future of transportation, promising cleaner air and freedom from costly fuel imports. However, in Pakistan, the electric dream faces a harsh reality. Despite ambitious government targets and the global hype, a drive through Pakistani streets shows that EVs remain a rarity. Even with the recent influx of Chinese vehicles, the price points are prohibitive for most buyers. This suggests that hybrids – cars that use both fuel and battery power – may actually be a more practical stepping stone. Let’s take a detailed look at why.

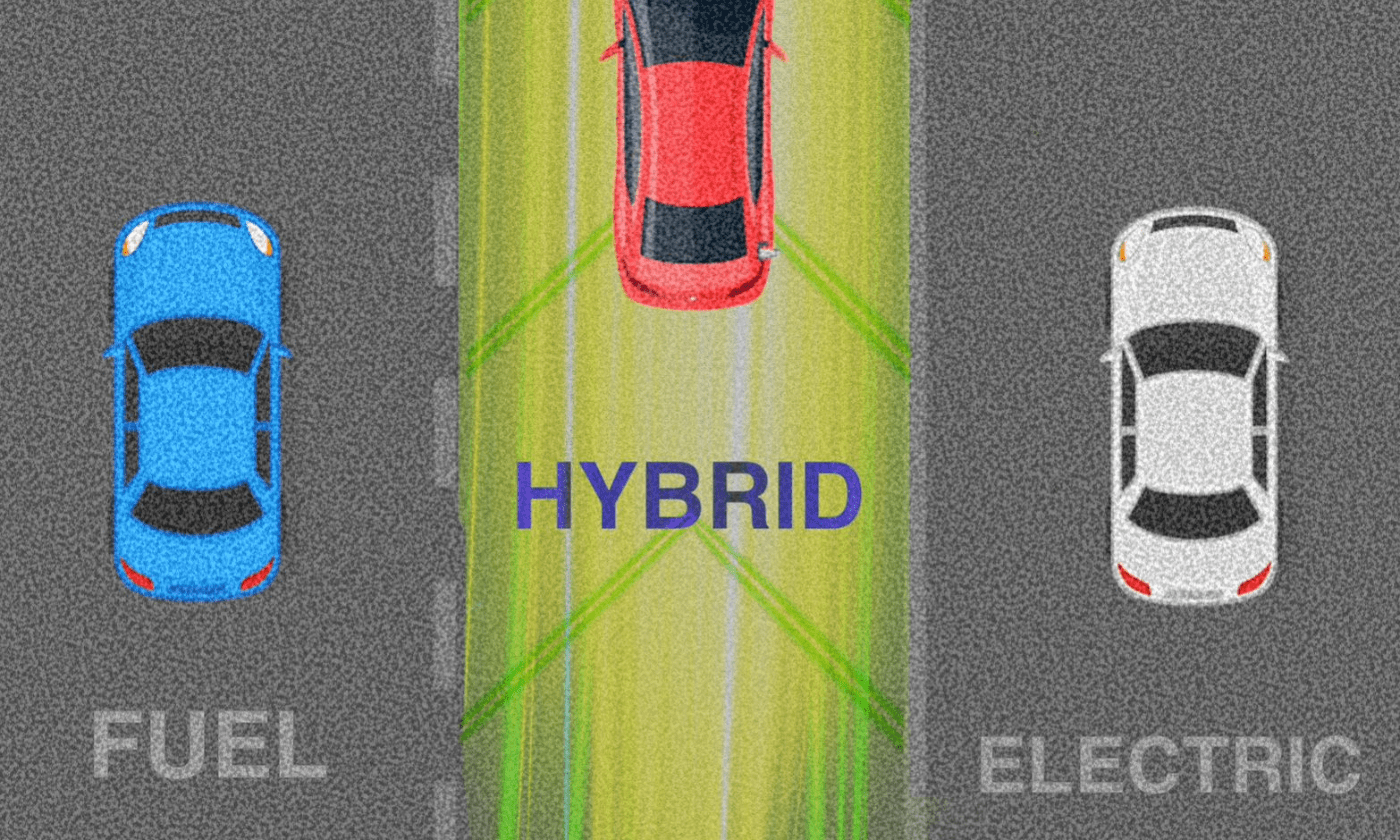

Here, it is essential to understand the three types of automotive powertrains that drive most cars: conventional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), and fully electric vehicles (EVs).

1. ICEVs: These vehicles are powered solely by a gasoline or diesel engine. They rely on fossil fuels for energy, emitting greenhouse gases and pollutants during operation. ICEVs are the most common vehicle type in Pakistan, due to their affordability and established fuel infrastructure.

2. HEVs: They combine a conventional internal combustion engine with an electric motor. The battery is charged through regenerative braking and the engine itself, so no external charging infrastructure is needed. HEVs are more fuel-efficient than ICEVs and emit fewer pollutants, making them a practical middle ground in regions where charging stations are scarce.

3. EVs: They are exclusively powered by an electric motor, drawing energy from a large rechargeable battery pack. EVs produce zero tailpipe emissions and are considered environmentally friendly, but require charging stations and reliable electricity. Their batteries are usually made of lithium-ion, the mining and transportation of which are largely dependent on fossil fuels.

EV Hype vs Pakistan’s Reality: Pakistan’s government rolled out its first National Electric Vehicle Policy in 2019 with lofty goals: 30% of all vehicles running on electricity by 2030 and transforming 3,000 CNG stations into charging points. Since then, there have been multiple revisions of the policy as the targets proved overly optimistic, and we are nowhere close to achieving them, and Pakistan has only a tiny fraction of vehicles on the road that are electric. The vast majority of EV models launched in Pakistan cater to a wealthy niche – costing upwards of Rs 20 million, well out of reach of the average consumer. Recently, there has been an influx of small EVs like the Honri and Rinco Aria under the four million price point, which would be an economical choice for people looking to buy either the Suzuki Wagon R or Alto at a similar, if not lower, price point.

Sparse Charging Infrastructure and Range Anxiety: The reason the Honri or Rinco will have a hard time competing with the combustion engine Alto is the lack of charging infrastructure. Few public charging stations are available, and not all apartment buildings or homes would be able to install charging points for all residents. At a national level, projections to install 3,000 stations have fallen flat – as of 2024, the total number of public charging stations is less than the number of members of the Pakistan cricket team. This scarcity is not just a minor inconvenience. Imagine planning a road trip from Karachi to Islamabad, only to realise that charging points are virtually nonexistent along the route. Even within cities, long queues at the few available stations are common, leading to frustration among the few EV owners. This lack of infrastructure feeds ‘range anxiety’ – the fear of running out of power mid-journey with nowhere to plug in.

The Affordability Gap: EVs are expensive, and with GDP per capita hovering around $1,500, even a moderately priced EV ($25,000 or eight million rupees) is out of reach for most people, and the electric cars currently on sale skew heavily towards luxury models. The other challenge is that most people don’t understand the math and the cost savings, given how new this market is. Say a buyer for an Alto is comparing whether the cost of ownership of an Alto over five years would be the same or more than an Honri or a Rinco Aria. The biggest saving is the fuel bills and maintenance, which is easy to calculate and compare to the charging cost. But what is unpredictable is the resale value of the EV after five years – and this could completely destroy any financial gains for the owner, making it useless to purchase such a vehicle. If the Audi e-tron and Porsche Taycan resale values are any benchmark, then there is proof that EVs do not hold value at the high end because of concerns about battery life and replacement costs. Does the same hold true for the low end of the market?

An Unreliable Grid and Load Shedding: Even if one can afford an EV and find a charger, there is another problem. Will there be electricity available to charge it, given that chronic load shedding is a part of life? Charging an EV at night can be problematic if power cuts hit, leaving the battery far from full by morning. In cities like Karachi and Lahore, load shedding can last up to eight hours, and voltage fluctuations are common. This means that even if a charging station is available, it might not work consistently. Wealthier homeowners might install backup generators or solar panels, but that is not a practical solution for most.

Fuel Subsidies and Convenience: Fuel at the pump has often been kept relatively cheap due to government intervention. When petrol is, say, Rs 250 per litre and electricity is costly, the incentive to switch to an electric car for fuel savings is weaker.This pricing disparity makes conventional fuel more attractive for mainstream consumers. Moreover, Pakistan’s vast network of petrol stations (found even in remote areas) ensures that drivers need never worry about where to refuel, even if that fuel has been smuggled in through our borders. In contrast, charging points for EVs are clustered in a few urban areas, making long-distance travel daunting.

A Missing Local EV Ecosystem: Pakistan’s auto industry is geared toward assembling traditional cars from imported kits. For EVs, the critical components – batteries, electric motors, and power electronics – are not made domestically at any scale. This reliance on imports increases costs and dependency on global supply chains. For example, lithium-ion batteries are primarily imported from China. Any disruption in trade or increase in import duties can significantly affect pricing, making EVs even less affordable for consumers. Localisation is a big part of the domestic auto industry’s strategy to stay competitive; however, it will be hard at the onset to localise for the kind of electronics EVs require.

A More Realistic Bridge to Sustainability: Hybrid vehicles combine a gasoline engine with an electric motor, dramatically improving fuel efficiency compared to standard cars. Crucially, they do not require a charging infrastructure. Hybrids can reduce fuel consumption immediately without waiting for charging stations to become widespread. Unlike EVs, hybrids do not require drastic changes in driving habits or infrastructure. Today, a number of new entrants in both the car and SUV segments, like the Corolla Cross, the Hyundai Santa Fe and Kia Sorento offer new hybrid alternatives that can offer the peace of mind of a gasoline engine with savings close to those of an EV minus the hit of depreciation and concerns of battery replacement costs. If you look at the used imported car market, the options increase tenfold.

Policy Recommendations:

Prioritise hybrid incentives in the short term and offer tax breaks or incentives on imports.

Support local assembly and manufacturing of hybrid and EV components. Build EV infrastructure step-by-step, focusing on urban centres and motorways. Strengthen the power grid.

Focus on two- and three-wheeler electrification, which offers quick wins in fuel savings.

Public awareness campaigns to build confidence in hybrid and EV technologies.

Mobility and transportation remain a major challenge across Pakistan, even if the recent developments of Lahore and Islamabad are the exception. The population needs cost-effective and fuel-efficient solutions to stretch their monthly income as much as possible. Today and for the foreseeable future, the hybrid electric vehicle is the one that offers the best middle ground and the one I would bet on.

Faizan Syed is Founder and CEO, East River. faizan@eastriverdigital.com

Comments (5) Closed