Screens and Entertainment

In March 2002, the PEMRA (Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority) Ordinance saw the opening up of the media to privately owned TV channels and FM radio stations. Very soon, audiences were exposed to a slew of news and current affairs talk shows and entertainment programming ranging from music, sports, food and, of course, the ubiquitous Pakistani drama series.

FM channels abounded, and a new generation was exposed to the enjoyment of radio. If this period was seen as one of booming media, what followed less than 10 years later in the shape of social media content and streaming services was even more explosive. The result? A relentless quest for content that sticks; a slew of new content creators (Millennials and Gen Zers); a fundamental change in advertising formats; and a fragmented audience scattered across multiple screens high on ad avoidance.

Leading the change was YouTube, providing a bridge for audiences to migrate from TV to digital. At the same time, vloggers started uploading a stream of new content. Social media platforms followed quickly, moving from static, textbased posts to videos, a shift amplified by TikTok. Originally seen as a low-brow medium suited to teenagers, TikTok has amassed huge audiences across the generational divide and along with Instagram, it is perhaps the most potent social media advertising medium so far. Along the way, social media formats changed, moving from videos to reels.

In this mix, YouTube continues to provide end-to-end programming (audiences can watch the entirety of a programme), while social media offers snippets of programming – although conceivably one can almost watch an entire sitcom episode thanks to an algorithm that diligently pumps into our feeds more of what we like. The result is that Boomer or Gen Z audiences have changed the way they consume content – which is free, where and when they like and free to skip ads – forcing advertisers to repackage and refocus their communication. So far, advertisers have been unable to find the winning sticky formula, although they maintain that their communication is effective. Maybe, but they are unlikely to win any awards.

In content terms, the oft-criticised Pakistani drama remains beloved by audiences across generations and is keeping production houses in business. The stories remain mostly stereotypical and the number of episodes is ridiculously high. Yet, beloved they are, and with the global reach afforded by YouTube, they are worth the investments made in their production. This success may also account for the complacency that sees winning formulas repeated again and again. Social media has fostered a host of new content creators and podcasters. Not all have talent, but those who do, need to be encouraged to go beyond making reels. In this regard, Pakistan’s entertainment industry has a role and a duty to perform in terms of talent spotting and mentoring. It is perhaps in the confluence between these new and passionate content creators and an industry that, despite some shortcomings, remains vibrant, that a reenergised and vigorous Pakistani entertainment industry will emerge.

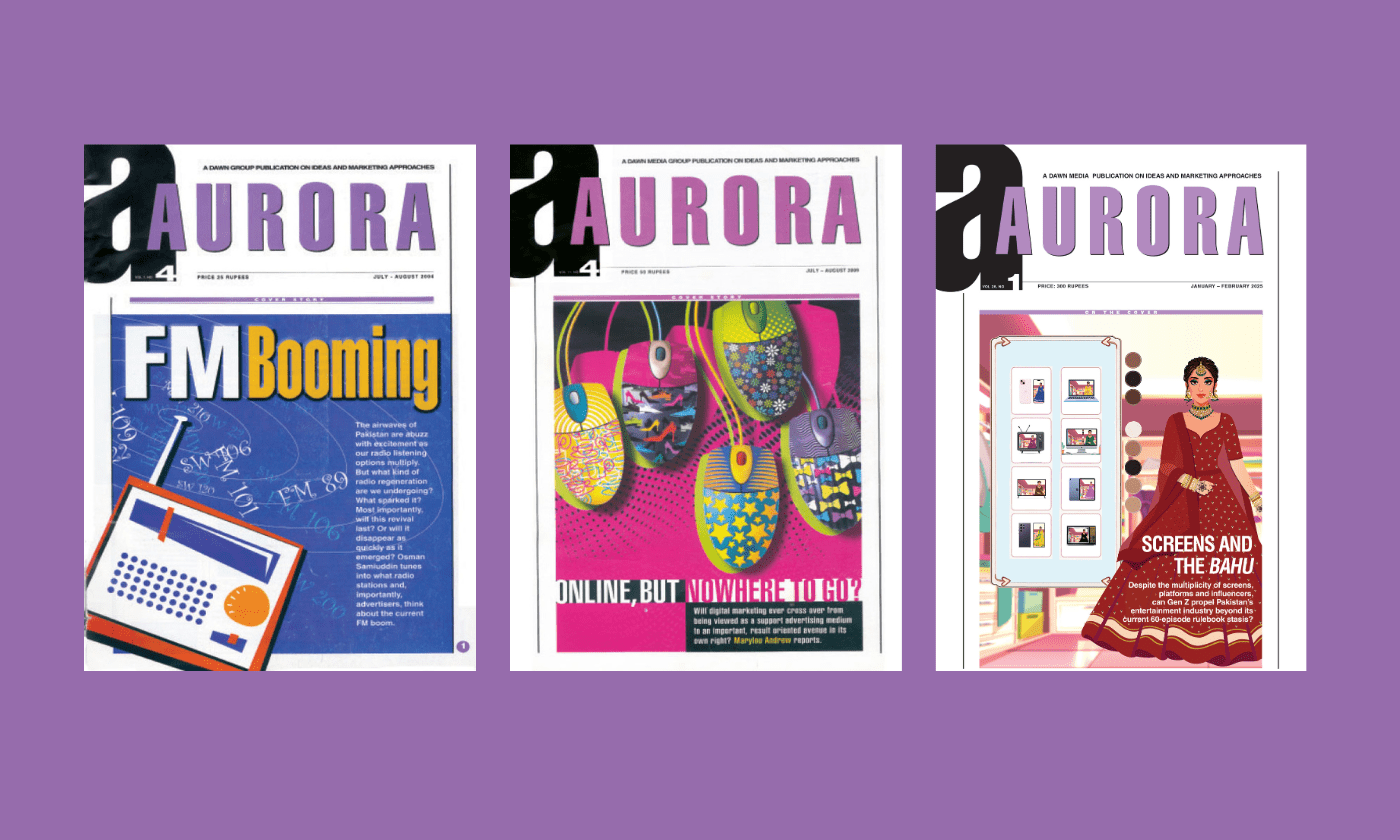

From Aurora’s archives

INTERVIEWS

Abdullah Kadwani & Asad Qureshi, Directors, 7th Sky Entertainment

Abdullah Kadwani & Asad Qureshi, Directors, 7th Sky Entertainment

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, CEO, SOC Films

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, CEO, SOC Films

PROFILES

Pakistan’s Storytelling Powerhouse: Farhat Ishtiaq, author and screenwriter

Pakistan’s Storytelling Powerhouse: Farhat Ishtiaq, author and screenwriter

Upholding His Mirror to Society: Sarmad Khoosat, actor and director

Upholding His Mirror to Society: Sarmad Khoosat, actor and director

ARTICLES

Bringing Community Radio to Pakistan – Javed Jabbar

Bringing Community Radio to Pakistan – Javed Jabbar

In Search of Lovers – Hasan Zaidi

In Search of Lovers – Hasan Zaidi

How to waste money, bankrupt channels and drive audiences crazy? – Syed Amir Haleem

How to waste money, bankrupt channels and drive audiences crazy? – Syed Amir Haleem

Why the Reports of TV’s Death Have Been Greatly Exaggerated – Urooj Hussain

Why the Reports of TV’s Death Have Been Greatly Exaggerated – Urooj Hussain

Comments (0) Closed