In Search of Lovers

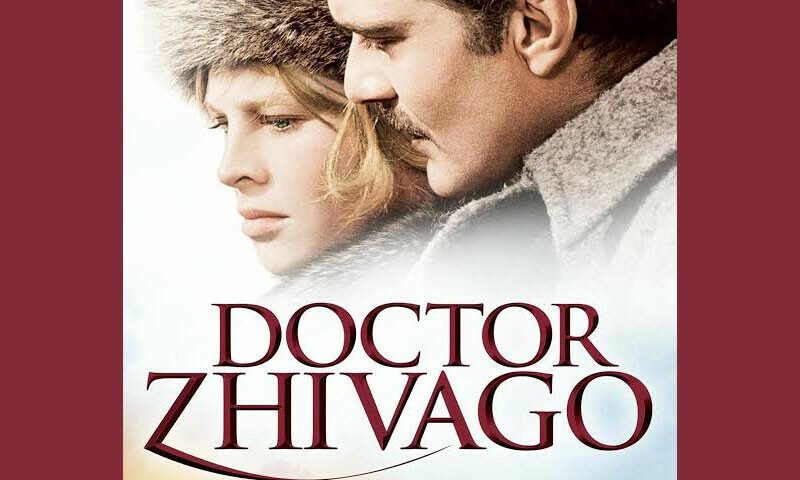

My first recollection of the cinema was watching David Lean’s Dr. Zhivago in Karachi’s Capri Cinema as a child with my parents. I still remember the feeling one of the scenes had on me: an early morning shot of horseback riders galloping through a foggy forest bathed in blue light. I was fascinated. But not just with the stunning, evocative visuals. It was also the feeling of sitting with a ‘full house’ of strangers in a darkened auditorium, collectively engrossed in what was playing out with flickering light on the giant screen in front of us. If I look back now, I think that was the beginning of my love affair with the cinema.

The dark phase for Pakistani cinemas and film, which began with the advent of the military dictatorship of General Zia in 1977, resulted in people gradually losing interest in going to the cinema to watch a film (although not in watching films). The marginalisation of film as a creative medium during that time and the subsequent degeneration in the social environment of cinemas, coupled with the arrival of home video equipment, strict censorship and rampant piracy, encouraged more and more people to stay home to watch films, at most with their family or a few close friends. What all this meant was that the majority of Pakistanis today – it would do us well to remember that more than half of the current population of Pakistan was born after 1985 – have never experienced the thrill that some of us felt when we all dressed up for the special ‘outing’ that cinema provided.

Of course, home video has made huge inroads all over the world, and television viewers have many, many more channels to choose from than they ever did before. The rapid expansion of the World Wide Web since 1994 has provided another avenue of activity and entertainment. But it is also true that people in Pakistan – and young people in particular – are also increasingly looking for avenues of activity outside their homes. They long for the chance to go out with their friends to places other than restaurants and also to be part of a larger collective that is enjoying itself.

When we began the KaraFilm Festival in 2001, we were not sure what the response would be like. It had been decades since the last festival of this sort in Pakistan, and we were not even certain that we could reverse a socialisation that had become ingrained over more than 20 years. But the enthusiastic response to even that first three-day festival convinced us that we were on the right track. Since then, we have seen exponential growth, with every subsequent festival seeing audience participation almost double from the previous year.

The response of the youth, in particular, has been stupendous. Hundreds offer to volunteer every year to help with the running of the festival. Some run entire weblogs discussing the merits and demerits of the films they see at the festival. Others have chosen to take up courses in newly established film departments of arts institutions and to make films themselves. We are constantly inundated with emails from all over Pakistan asking us for advice about how they can ‘break into’ the filmmaking scene.

What this has shown us, and those who care to understand trends, is that there is a genuine demand for social film-related activity and for facilities for creative expression. The success of commercially released films such as Majajan, King Kong and Pirates of the Caribbean 2: Dead Man’s Chest – the latter two of which were released in Pakistan very shortly after their international debuts – only goes to show that people are willing to come back to the cinema as long as what they are being offered, both in terms of the product on display and the viewing experience, is halfway decent. If international films can be released simultaneously or within a month of their international release, people will gladly forego their pirated versions for the large-screen experience.

In short, there is a ‘market’ for good cinema and a massive potential for using films to reach out to people, particularly the youth. At a time when channel surfing on television has become the norm and the recall value of increasingly similar television programming is falling, nothing beats the hype and glamour surrounding a major film release. People make a conscious decision to go see a film in the cinema, for those looking for a ‘captive’ audience; cinema audiences are already predisposed to listening.

But of course, much more needs to be done before this nascent revival of ‘cinema culture’ can take root. The first and foremost thing that needs to happen is for more cinemas, particularly multiplexes, to be established in various locales that are nearer people’s homes. Existing cinemas are too few, located too far from many people’s homes and sometimes poorly managed and in a bad state of repair. Some companies are already in the process of investing in modern multiplexes in Karachi, Islamabad and Lahore. The thinking behind it is simple: people like to go out to have a good time, prefer choices, and want to be facilitated in their evening experience. What this means in practice is that the environment of the cinemas should be clean, comfortable and women-friendly; that there are multiple film offerings to suit different tastes; and that it should be possible for people – if they choose – to have a meal nearby before catching a film or vice versa. Establishing new cinemas requires some investment, but the possibilities for marketing at the venues and the returns on the investments are quite substantial.

Secondly, the quality of films being offered must improve to attract people back to the cinemas. Admittedly, the big slump in the quality of Pakistani films generally being made these days requires intervention on many fronts, and the results will take some time to become apparent. Again, there are initiatives already in place. It is in the interest of those looking to capitalise on the cinema-going market to invest in various endeavours to improve the quality of domestic films, including festivals, training institutions and films themselves. However, something else will need to fill the void of available products for the cinema circuit until that time. As mentioned before, the earlier release of Hollywood films will help satisfy one end of the market. For the mass market, however, the best option for immediate products will remain Bollywood films, which are immensely popular in Pakistan because of their cultural affinity and common language. This will happen eventually despite the protestations of a small minority opposed to anything to do with India. It is our job to make the government understand how our own cinema and youth may benefit from the expansion in the cash flow that is sure to come from the reopening of our cinemas to even a select number of Indian films.

In addition, at the level of government, arbitrary and outdated censorship codes need to be revamped, bureaucratic hassles in producing films need to be curtailed, and incentives need to be provided to investors in local films and cinemas. Some of these issues are already being taken up with the government. But the pressure for change must come from the people who need the change and can see the potential of cinema, both for business and for the youth of Pakistan.

We are fond of complaining about the quality of Pakistani films and of the state of our cinema circuits but do little about it. Fortunately, there is vast untapped potential in the young people of Pakistan. Someone has to step up to the plate, however, and help it be liberated. Who knows, perhaps some other child will begin a love affair with cinema and make us all proud of Pakistan’s creative talent.

Hasan Zaidi is a filmmaker and Festival Director of the KaraFilm Festival.

Comments (0) Closed