The Supremacy of Brands

Brands as powerhouses of consumer wants came into their own in Pakistan in the eighties. The seventies saw the consolidation of the advertising agency as the client’s advertising communications partner. The launch of PTV in the sixties was a game changer – in the same order of impact magnitude as the internet would have in the nineties – with clients and their agencies scrambling to promote their products and services on this new and exciting medium. In those days, agencies handled the entire gamut of their clients’ marketing requirements – concept creation, copy and script writing, media placement, film and production.

By the late seventies, as the effects of a nascent globalisation began to reach Pakistan, a transformation of the agency-client relationship began to take place, driven by the notion of branding – the need to establish product differentiation in the consumer mind. Good products became ‘brands’ that spoke to consumer needs and aspirations. Successful branding meant creating a distinct emotional and long-lasting bond. Buying a product was no longer just a utilitarian act; it was a statement of aspiration. To create this distinction, clients divided their brand portfolios among different agencies, with no one agency handling the entirety of the portfolio.

Understanding consumers became the key to brand success. Part of it lay in reaching consumers through every available medium, giving Marshall McLuhan’s expression “the medium is the message” the credence it deserved. Every medium was exploited to its fullest potential, and the consumer journey and experience became the lynchpin of every marketing strategy.

Then the internet connected the world in a way until then unimaginable. Consumers were exposed in real-time to whatever was going on worldwide. New products, new trends, new lifestyles – everything was there to behold and aspire to. Advertising became frenetic, leaving clutter everywhere while creating incipient fatigue among consumers who were tired of being exposed to relentless promotional messaging. Suddenly, brands had to do a lot more than deliver aspirations. Consumers started to ask for something extra from their brands. Quality and superiority were not enough; brands had to take a position and have a purpose.

In the battle for supremacy, multinational brands led the way in Pakistan. They brought in media buying houses and introduced the skills and tools essential for effective placement in a fragmenting media environment. Their affiliates introduced new tools, systems and learnings.

The more interesting stories are the national brands – Candyland, EBM, Engro, National Foods, Lucky Group, Shan and Tapal, to name just a handful. Brands that absorbed best practices in terms of their products, professionalism and ethical practices. Today, these brands shine as examples of what national brands can achieve. Along the way, some worthy brands have lost their market pre-eminence – Capri, Tibet – while others vanished in the fray. This said, for the most part, brands in Pakistan have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. They have not only met the challenges of changing consumer expectations; they have weathered the multiple economic storms the country has faced, especially in the last five years.

From Aurora’s archives

INTERVIEWS

Amir Paracha, CEO, Unilever Pakistan

Amir Paracha, CEO, Unilever Pakistan

PROFILES

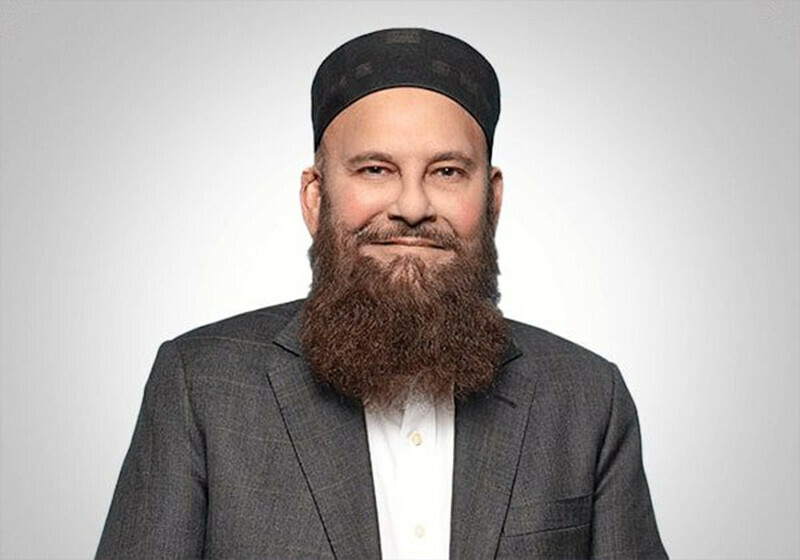

The Master of Spices: Sikander Sultan, Founder and Chairman, Shan Foods Industries

The Master of Spices: Sikander Sultan, Founder and Chairman, Shan Foods Industries

ARTICLES

What Makes a Pakistani Brand? – Sheikh Adil Hussain

What Makes a Pakistani Brand? – Sheikh Adil Hussain

Comments (0) Closed